A recent global threat report has piqued curiosity around how threat actors prioritize attack surfaces for their campaigns. CybersecAsia investigates…

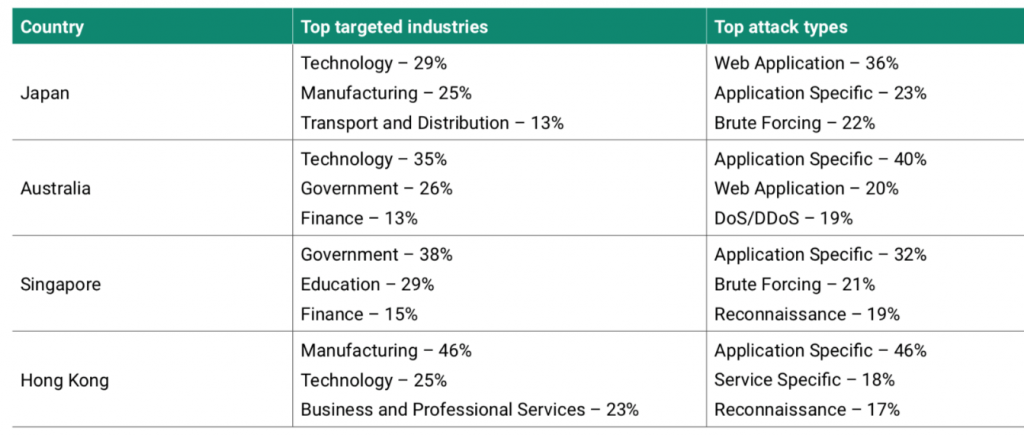

Across the Asia Pacific region, the technology sector is one of the most targeted sectors by cyber attackers. Singapore however, stands out as a slight anomaly in this regard, with the top sectors being targeted being government and education, possibly indicating a different objective for cyber attackers.

The table below, taken from NTT Ltd’s recent 2020 Global Threat Report, shows the cyberattack landscape studied from the period October 1, 2018 to September 31, 2019.

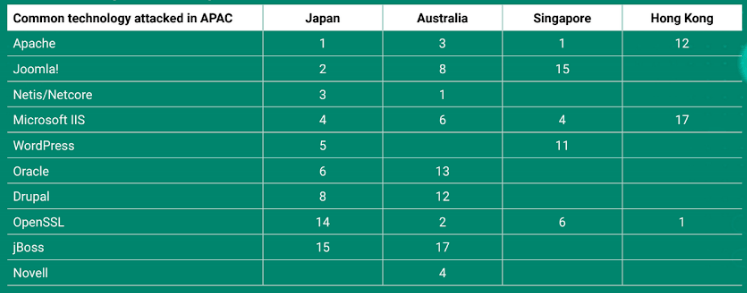

Noting from the figures that different industries across the region attracted more of certain types of attacks, and also zooming in on some of the threat report’s recommendations on content management systems and patch management discipline, CybersecAsia managed to contact NTT Ltd’s Director of Cybersecurity, Neville Burdan (referred to as NB from here on) for some insights.

CybersecAsia: Why do you think the Govt and Education industries in Singapore are such prominent targets for cyber-attackers but not in the other APAC countries?

NB: While both the government and education industries were the most targeted in Singapore, it bears mentioning that it does not mean such industries were not attacked in other countries, but rather, they were attacked at a higher rate in Singapore.

For instance, the NTT 2020 Global Threat Intelligence Report revealed that attacks against the government and education sector accounted for 37% of attacks in Australia as well. This trend possibly indicates that these industries in Singapore had the more vulnerable technology which attackers took advantage of. One example of this would be the second most commonly exploited Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVE) targeted in CISCO devices, frequently found in government infrastructures (CVE-2018-15454 Cisco ASA SIP vulnerability).

Government organizations across nearly every region analyzed were plagued by application specific attacks and it was a common trend across the entire industry.

In the education industry, Apache products, especially Tomcat, are found in many educational organizations, and were a common point of vulnerability that was highly targeted throughout every region. Such organizations in Singapore were also marked by high amounts of brute force attacks with 59% of all attacks targeting the education sector in Singapore.

CybersecAsia: Similarly, can you shed some light on why the different industries of APAC countries attract certain modes of attacks? (E.g., why is Australia the only one that attracts DDOS?)

NB: The types of threats that different industries and countries attract is highly dependent on the web-presence and technologies in use.

Technology organizations for example, experienced the single most exploit attempts of any vulnerability in Australia because their systems proved vulnerable to CVE-2017-3731, a denial of service in OpenSSL. The reasoning behind this is that attackers often select specific targets with exposed vulnerabilities which they can exploit. As a result, organizations that use web technologies tend to have high volumes of vulnerabilities exposing them to more attacks.

CybersecAsia: What are the most prominent malware currently found in Singapore, HK, Australia and Japan, and how can organizations defend against them?

NB: This is an interesting problem with a few different facets to it, with there being the most common malware by type, as well as the most common specific malware. As a family, the single most common type of malware detected across the APAC region was some form of vulnerability scanner like muieblackcat or zmeu. The problem is that these capabilities are often implemented into other malware to facilitate target identification and spreading.

To combat this and limit the effectiveness of vulnerability scanners, there are a variety of techniques to be implemented and most notably among them, involves maintaining an active patch management program designed to limit the numbers of vulnerabilities existing in an infrastructure.

Another would be aggressive network segmentation and isolation. If an organization can segregate one subnetwork from another, it can dramatically limit the effectiveness of scanners attempting to run across segments.

On the single most common specific malware across APAC, it would then be the botnet IoTroop, followed closely by the ChinaChopper webshell. IoTroop is an IoT-based botnet, so ensuring that your IoT infrastructure uses good security practices is imperative. Hardening your IoT environment is likely not a matter of ‘patches and fixes’ as it is of establishing a security architecture designed to protect your IoT devices and your entire infrastructure. This is not a simple fix, but the most important steps to begin with are removing default credentials and changing default passwords.

ChinaChopper, on the other hand, is a webshell that grants access to the attacker. It is most likely installed ‘post compromise’, which means that the organization would have already been breached. The best course of action then would be implementations similar to those previously mentioned to guard against vulnerability scanners—apply timely patches and weave in a reasonable amount of network segregation to protect organizational segments from other compromised segments.

CybersecAsia: Japan is unique in its strongly-entrenched use of Japanese in its software, operating systems, communications, etc. Does this use of a difficult or unfamiliar language pose any challenges or stimuli to hackers? APTs?

NB: Although a language barrier can interfere with an attacker’s efforts, it is worth keeping in mind that an exploit against, for instance, an remote code execution in Joomla! is not affected by the language. The exploit works the same way, targets the same configuration, the same software, the same protocol, regardless of the language of the site operator.

The language barrier however, is one of the big reasons a black market exists for exploit kits and tools. To attack a site in Japanese, the attacker need not be literate in the said language. They only have to simply subscribe to a tool which offers Japanese support.

Also, a significant number of threat actors select targets that are geographically close to them. For instance, an attacker targeting Japan may be from Japan, China, or even Vietnam and is more likely to know Japanese than an attacker from Brazil.

The two areas in which language is most likely to impact an attack is in the case of social engineering or phishing attacks—but that is also why a threat actor would buy these services from someone else.

For instance, if a malicious actor does not know any Japanese at all, it is still possible that they find themselves with detailed access to the most sensitive data in the most sensitive database within the targeted organization, but not realize it because they do not understand the context of the data.

This does not mean the data is safe, though. In such a case, the attacker is more likely to simply extract and exfiltrate as much of the database as possible, then worry about what that data is at a later time.

CybersecAsia: Tell us more about the exposure of CMS systems as mentioned in the threat report. How does a media setup, for example, tighten its CMS security?

NB: The point of Content Management Systems (CMSs) being attacked is not as much that CMSs are vulnerability laden targets, but more so that CMS are often accessible to the outside world. This gives attackers an opportunity to take advantage of the available access and the vulnerabilities that come with it.

Every CMS that NTT Ltd. has analyzed has configuration or hardening guides which help make it practical to successfully implement these suites in reliable manners. Unfortunately, more often than not, those guidelines are not followed.

If a CMS suite is properly installed with appropriate permissions; with default credentials removed and remaining credentials having strong passwords paired with two-factor authentication, while being up to date with patches—that CMS can be a perfectly acceptable and working solution.

So, the single best recommendation for any setup using CMS suites is to follow the appropriate installation and hardening guidelines for the suite you are using, then complement that with an appropriate patching program and network segregation/isolation.

CybersecAsia: One infographic in your report notes that patch-management is a major gap in cybersecurity. Yet, patches themselves have been known to be fallible. Some have even been known to cause hardware failure or bricking. How does NTT plug this patching management gap and mitigate any potential problems in the patches?

NB: While patches are important, the active management of an effective patch management program is even more so. It is true that some patches have created problems equal to or greater than the problems they were designed to fix. However, just like any security control, patches need to be prioritized, and evaluated —including testing—appropriately.

In each case, the organization needs to weigh the risk of applying that patch against the risk of not applying that patch at a given time for the system under consideration. This likely means different considerations for systems which operate for the convenience of the organization versus systems that are critical to organizational survival.

Another consideration as part of this process is the proper evaluation of the patch, and determining what level of testing is appropriate for the system in question. It may be appropriate for an organization’s risk tolerance and system criticality to immediately apply a patch, but it may also be just as appropriate for that same organization to never apply a patch.

In any event, the organization should maintain a reversion plan for all updates made to critical systems in the event of a failure.

CybersecAsia thanks Neville for his valuable insights.