How Bluetooth contact tracing apps work, what it means for privacy, and what you should do about it.

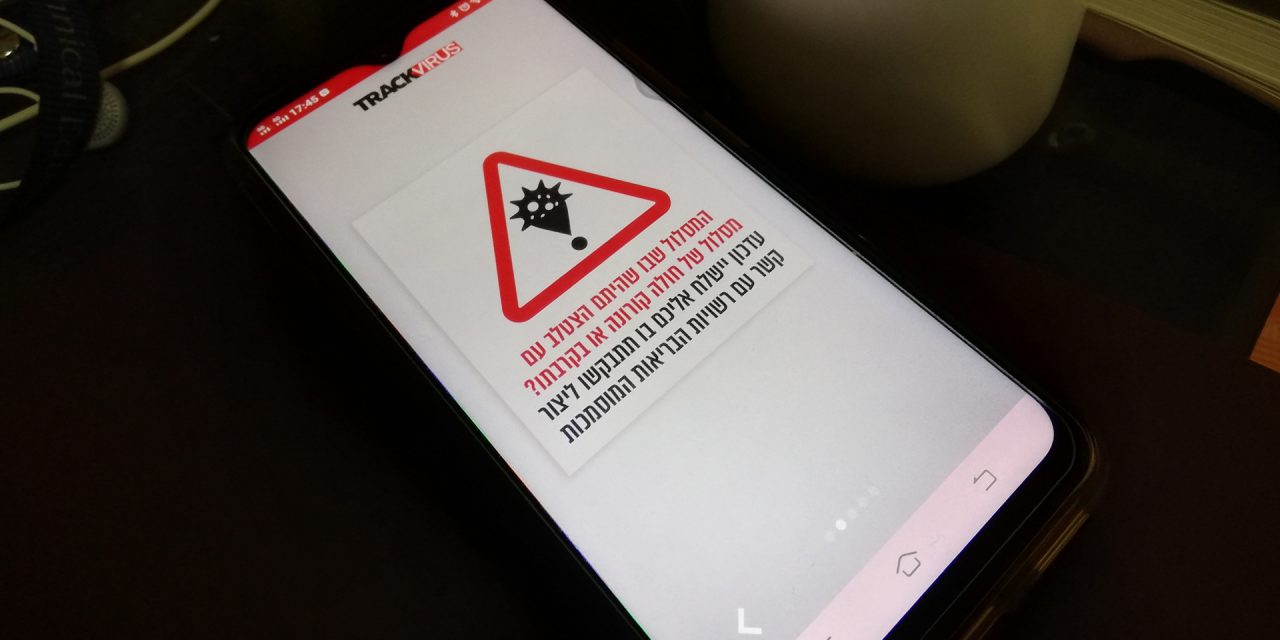

As more countries move along to develop contact tracing apps to track potential COVID-19 infections between people, a question comes to mind: what does this mean for the man in the street – or, to be more precise, the person working from home?

While contact tracing apps help the health authorities in containing the spread of infectious diseases, will downloading the app sacrifice one’s privacy?

Niels Schweisshelm, Technical Program Manager, HackerOne shares some answers to the pertinent questions we have about these mobile apps.

How does these contact tracing apps work?

Schweisshelm: Contact tracing apps allow users to upload Covid-19 test results. It is then possible to leverage Bluetooth to determine with whom you have been in contact with; these individuals will then be notified of potential exposure to Covid-19. Additionally, you will be notified if you have been in recent contact with individuals who tested positive for Covid-19.

What will these apps be tracking?

Schweisshelm: Not only will these contact tracing apps track and store your location; they will also store PII [personally identifiable information] such as names and phone numbers, as well as medical information. Last but not least these apps will track and store data about individuals you have been in contact with recently. These apps will cross-reference movement data from individuals with medical data to determine if you have been in contact with individuals that have tested positive for Covid-19 and vice versa.

What are the potential security implications or privacy concerns for users who download these apps?

Schweisshelm: Data that will be used in contact tracing apps is immensely valuable for threat actors; having PII, location data and medical data belonging to an individual allows cybercriminals to set up elaborate spear-phishing attacks that will be difficult to distinguish from legitimate medical information. Additionally, governments storing and processing this data could use the data for different purposes; e.g. to verify if you have been in contact with interesting individuals or if you were in the vicinity of a crime scene around a certain time.

Are there any alternatives? Manual tracking devices perhaps?

Schweisshelm: There are alternatives currently out there such as Simmel. These non-centralized applications only allow local storage of sensitive medical and personal data until the user specifically enables the sharing functionality. However, these alternatives are based on Bluetooth; so any vulnerability in the Bluetooth protocol or its implementation could still enable attackers to potentially access the sensitive data stored on the device.

What advice do you have for those using these apps?

Schweisshelm: Now is even more so the time to treat your mobile phone as you would treat a laptop or desktop PC. Always install the latest security patches, use secure passcodes to lock your device and use a device finder tool to locate and/or whip your phone after losing it. Also, be careful which apps you install and what permissions you give those apps.