A comprehensive white paper shows how ransomware threat actors went bigtime and emulated state-sponsored attack methods.

Six months into the new decade, if we take a look back at 2019 ransomware attacks, we may discern a set of evolutionary trends. That year was dominated by increasingly-aggressive ransomware campaigns, with its operators resorting to more cunning tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs) to get their victims shell out the money.

Group-IB, a Singapore-based cybersecurity company that specializes in preventing cyberattacks, noted that the number of ransomware attacks increased by 40% in 2019 over the previous year, while devious techniques employed by the attackers had helped them to push the average ransom by 10 times in just one year.

The greediest ransomware families with highest pay-off were Ryuk, DoppelPaymer and REvil. These findings come as highlights of a Group-IB whitepaper that closely examines the evolution of the ransomware operators’ strategies in 2019.

Big game hunting

Last year, ransomware operators matured considerably, having joined the ‘Big Game Hunting’ league that focuses only on high-value data and targets. Beyond just file encryption, more groups had started distributing ransomware, and Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS) adverts to focus their attacks on big enterprise networks rather than individuals.

TTPs employed by ransomware operators showed that they came to resemble what once was considered a modus operandi of primarily Advanced Persistent Threat groups: last year saw even trusted relationship- and supply-chain attacks conducted by ransomware operators.

Another trick that ransomware operators started emulate from APT groups was downloading of sensitive data from victims’ servers. It should, however, be noted, that unlike APT groups that download the info for espionage purposes, ransomware operators download it to then blackmail their victims to increase the chances of ransom being paid. If their demands were not met, they attempted to sell the confidential information on the black market. This technique was used by REvil, Maze, and DoppelPaymer operators.

Big Game Hunters frequently used different trojans to gain an initial foothold in the target network: in 2019, a wide variety of trojans was used in ransomware campaigns, including Dridex, Emotet, SDBBot, and Trickbot, according to the whitepaper.

Also, most ransomware operators actively used post-exploitation frameworks in 2019. For instance, Ryuk, Revil, Maze, and DoppelPaymer actively used such tools, namely Cobalt Strike, CrackMapExec , PowerShell Empire, PoshC2, Metasploit, and Koadic, which helped them collect as much information as possible about the compromised network.

Some operators used additional malware during their post-exploitation activities, which gave them more opportunities to obtain authentication data and even full control over Windows domains.

How it all began

In 2019, the majority of ransomware operators used phishing emails, intrusion through external remote services, especially through the remote desktop protocol (RDP), and drive-by compromise as initial attack vectors.

Phishing emails continued to be the most common initial access technique. This technique’s main admirers were Shade and Ryuk. Financially-motivated threat actor TA505 also started its Clop ransomware campaigns from a phishing email containing a weaponized attachment that would download FlawedAmmy remote access trojan or SDBBot, among others.

Last year, the number of accessible servers with an open port 3389 grew to over 3 million, with the majority of them located in China, the United States, Germany, Brazil, and Russia. This attack vector was popularized among cybercriminals by the discovery of five new Remote Desktop Service vulnerabilities, none of which however was successfully exploited. Dharma and Scarab operators were the most frequent users of this attack vector.

In 2019, attackers also frequently used infected websites to deliver ransomware. Once a user found themselves on such a website, they are redirected to websites that attempt to exploit vulnerabilities in, for example, their browsers. Exploit kits most frequently used in these drive-by attacks were RIG EK, Fallout EK, and Spelevo EK.

Some threat actors, such as Shade (Troldesh) and STOP operators, immediately encrypted data on the initially-compromised hosts, while many others, including Ryuk, REvil, DoppelPaymer, Maze, and Dharma operators, gathered info about the intruded network, moving laterally and compromising entire network infrastructures.

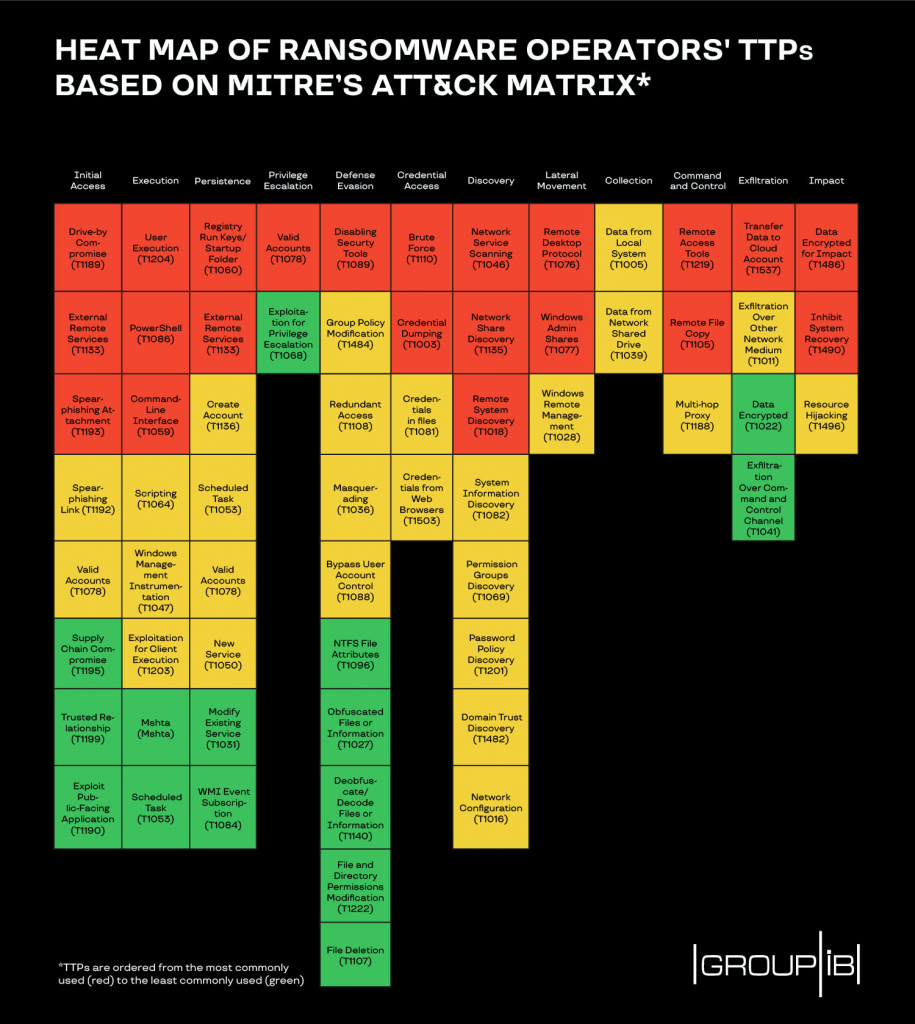

The full list of the TTPs outlined in the whitepaper can be found in the heat map, which is based on MITRE’s revolutionary ATT&CK matrix. They are ordered from the most commonly used (red) to the least commonly used (green).

Game-changer

After a relative lull in 2018, the year of 2019 saw ransomware returning at full strength, with the number of ransomware attacks having grown by 40%. The larger targets determined greater ransoms: the average figure soared from US$8,000 in 2018 to US$84,000 in 2019, according to the industry researchers. The most aggressive and greediest ransomware families were Ryuk, DoppelPaymer and REvil, whose single ransom demand reached up to US$800,000.

Commented Group-IB Senior Digital Forensics Specialist Oleg Skulkin: “The year of 2019 was marked by ransomware operators enhancing their positions, shifting to larger targets and increasing their revenues, and we have good reason to believe that this year they will celebrate with even greater achievements. Ransomware operators are likely to continue expanding their victim pool, focusing on key industries, which have enough resources to satisfy their appetites. The time has come for each company to decide whether to invest money in boosting their cybersecurity to make their networks inaccessible to threat actors or risk being approached with ransom demand and go down for their security flaws.”

Despite the vim showed by ransomware operators recently, ward off ransomware attacks is still possible. The measure include, among others, using a VPN whenever accessing servers through RDP, creating complex passwords for the accounts used for access via RDP and changing them regularly; restricting the list of IP addresses that can be used to make external RDP connections; and many others. More recommendations can be found in the relevant section of the whitepaper.