The disparities and loopholes of evolving national data privacy protection acts are a global minefield that businesses should prepare for next year.

From credit card details and medical records to private conversations and even dating preferences, the modern consumer entrusts an unprecedented number of organizations with their most sensitive information, hoping against hope that it will be stored on the digital equivalent of Fort Knox.

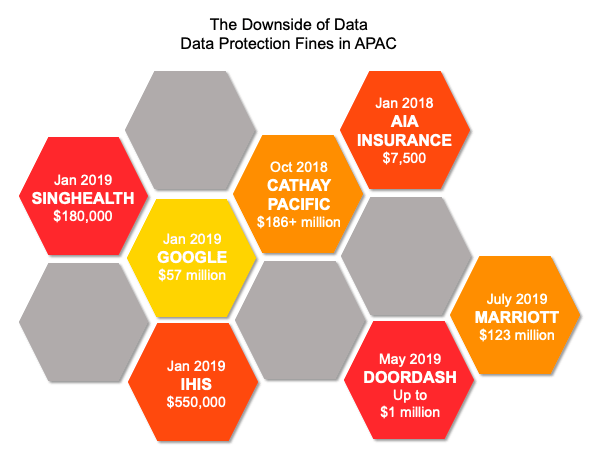

The reality, however, is that robust data privacy has thus far proven elusive. Almost 13 billion records in the US and Europe were breached over the last two years including those from Facebook, Google, and the US Postal Service. In the Asia Pacific region alone, this figure is close to 21 million records, including those from Cathay Pacific, SingHealth, Thailand’s TrueCorp, Australia’s DoorDash, and the Philippines’ Jollibee Foods and Cebuana Lhuillier—demonstrating once again that no network perimeter can keep motivated attackers at bay.

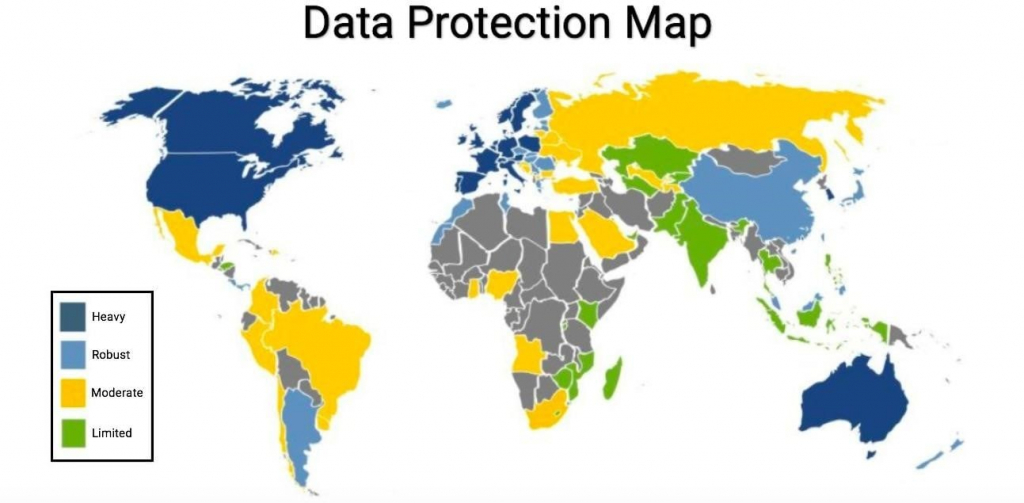

For governments whose principal responsibility is to safeguard their citizens, implementing a strong data protection regime is therefore as challenging as it is critical. At a time when cybercriminals find vulnerabilities in the most ostensibly airtight systems, these regulators have tended to shy away from mandating concrete security practices, since no one can anticipate which measures will repel the next unpredictable attack. Instead, most data protection laws default to ambiguous calls for “reasonable” “adequate” or “appropriate” cyber defences—language that arguably renders any breached company non-compliant by definition.

Ultimately, as governments attempt to address growing public concern over data privacy, the mere incident of having suffered a breach could be seen as grounds for significant fines. Avoiding these fines — and doing right by one’s customers—entails assuming that the bad guys will inevitably get past the perimeter.

GDPR goes global

The EU’s adoption of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in April 2016 was the watershed moment in the history of data protection legislation. Its enumeration of individual privacy rights, its 72-hour breach notification requirement, and its broad data protection directives continue to serve as a blueprint for countless others, such as Australia’s Notifiable Data Breaches (NDB) scheme, Brazil’s General Data Protection Law (LGPD), and Thailand’s Personal Data Protection Act (PDPA). The NDB scheme took effect in 2018 and the latter two regulations become enforceable in 2020, with major ramifications for companies worldwide.

Australia’s NDB scheme took effect from February 22, 2018, making it compulsory for all organizations under the Privacy Act 1988, particularly those with an annual turnover of A$3 million or more, to notify individuals whose personal information has been compromised. However, this responsibility also rests on the targeted organization to inform the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) should it encounter an “eligible data breach”. Serious data breaches will result in a business being slapped with up to 2,000 penalty units, of which the rate is indexed each financial year; while corporate bodies will incur up to five times more.

Brazil’s law, which will go into effect on August 15, 2020, is modeled closely after GDPR. Like GDPR, the law applies to all companies that handle the personal data of any of Brazil’s 210 million residents regardless of where these companies themselves are headquartered. Also, like GDPR, of course, the LGPD’s security clauses are open to interpretation. The law compels data handlers to “adopt security, technical, and administrative measures able to protect personal data from unauthorized access”, taking into account “the current state of technology”.

The PDPA in Thailand—effective starting on May 27, 2020—is similarly vague in mandating unspecified security measures. It parts company, however, in that violators face the possibility of criminal prosecution and even imprisonment for up to one year, on top of the payment of civil damages. Organizations classified as Critical Information Infrastructure (CII), including banks, telecoms, utilities, and hospitals, are regulated under Thailand’s separate Cybersecurity Act and its slightly more detailed obligations.

Checkmate for checkbox compliance

Between the hundreds of data protection fines levied under GDPR and analogous laws, the common thread is that penalized companies are deemed to have suffered a preventable breach. For instance, in the aftermath of the 2017 Equifax compromise that exposed the personal information of more than 140 million consumers, the company was found to have been in violation of the FTC Safeguards Rule, which compelled it to adopt security measures “appropriate to [the] size and complexity” of its digital infrastructure.

The US government concluded that the incident was “entirely preventable” if Equifax had performed a “routine” security update on the impacted database—an oversight that precipitated at least $1.4 billion in total damages.

The upshot of all these new laws, requirements, and fines is that the days of mere checkbox compliance are over. Breached companies can no longer throw up their hands and point to the list of perimeter security tools they had in place, particularly because attackers largely exploit user errors and misconfigurations that, while inevitable, also appear preventable in a vacuum. Rather, to achieve compliance in 2020, human teams need artificial intelligence to make sense of their dynamic digital estates.

By learning how each unique user and device normally functions while ‘on the job’, such cyber AI detects threats that are already inside the perimeter—before they cost the company in court.