One of 2024’s landmark ironies of cybersecurity is doing the wrong thing (a bad patch) at the right moment (automated installation)

On 19 July around the world, the critical infrastructures of government agencies, airports, hospitals, financial institutions, corporations, and other users of Microsoft Windows machines running on the CrowdStrike Falcon protection ecosystem were severely crippled.

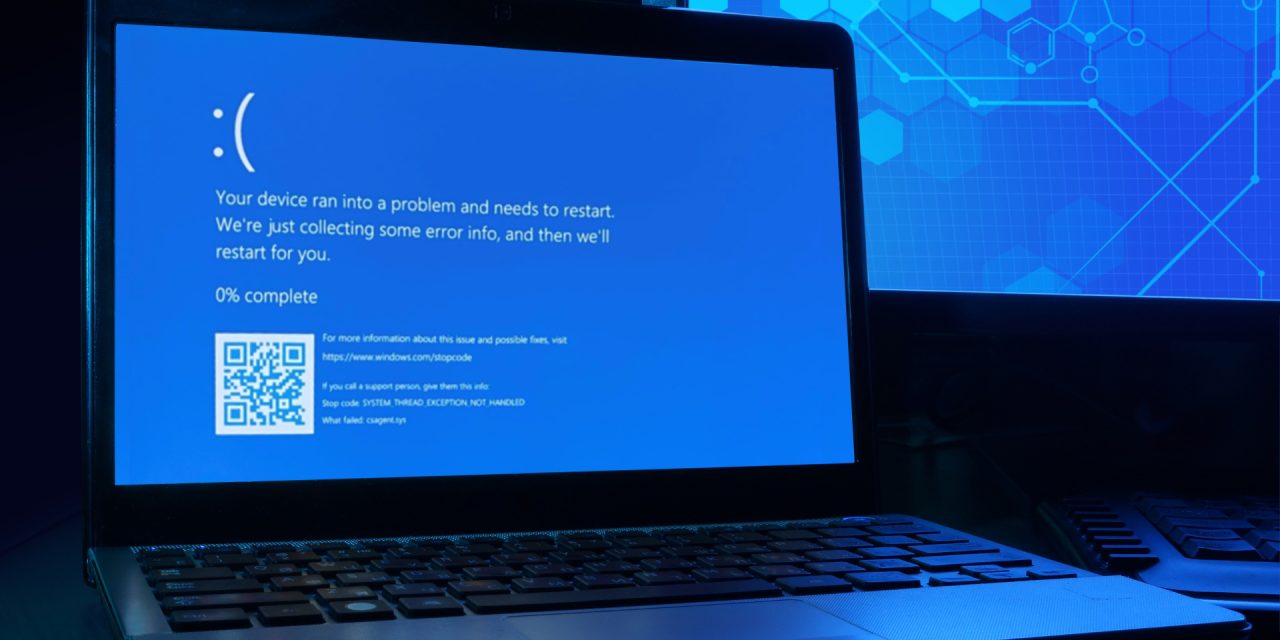

The resultant worldwide chaos has until now, 22 July, caused untold inconvenience and even damage to countless people and organizations despite CrowdStrike’s issuance of mitigative steps to bring affected Windows machines back to life after hours of blue-screen-of-death outage.

In the middle of the mayhem, scammers and phishing campaigns were already in circulation, taking advantage of the crisis to ensnare people into paying for quick fixes to the hardware crashes caused by an automatic update patch applied to Windows systems running on Falcon endpoint detection and response (EDR) software.

Because this is a security software, it requires a higher level of privileges to the underlying operating system, so a bad or faulty security update can result in a catastrophic impact. This event is unprecedented and the ramifications of it are still developing, according to Satnam Narang, Senior Staff Research Engineer, Tenable.

Not a cyberattack

Initially thought to be a coordinated global cyberattack, the outage has been officially attributed by CrowdStrike to a bad update patch rolled out globally to Microsoft Windows machines running its EDR software.

According to one cybersecurity expert, Jake Moore, Global Security Advisor, ESET: “Businesses must test their infrastructure and have multiple fail safes in place, however large the company is. This is typically referred to as a cyber-resilience plan. But as often it is with the case, it is simply impossible to simulate the size and magnitude of the issue in a safe environment without testing the actual network. The (incident) serves as a reminder of our dependence on Big Tech in running our daily lives and businesses. Upgrades and maintenance to systems and networks can unintentionally include small errors, which can have wide-reaching consequences.”

Another expert, Omer Grossman, CIO, CyberArk, told CybersecAsia.net: “The damage to business processes at the global level is dramatic. There are two main issues on the agenda: The first is how customers get back online and regain continuity of business processes. It turns out that because the endpoints have crashed – the Blue Screen of Death – they cannot be updated remotely and this problem must be solved manually, endpoint by endpoint. This is expected to be a process that will take days.”

The second issue is causation: the range of possibilities ranges from human error — for instance, a developer who uploaded an update without sufficient quality control — to the complex and intriguing scenario of a deep cyberattack, prepared ahead of time and involving an attacker activating a “doomsday command” or “kill switch”, according to Grossman.

A lethal lesson in software diversity

ESET’s Jake Moore noted that, this incident relates to “diversity” in the use of large-scale IT infrastructure. “This applies to critical systems like operating systems, cybersecurity products and other globally deployed (scaled) applications. Where diversity is low, a single technical incident, not to mention a security issue, can lead to global-scale outages with subsequent knock-on effects.”

Yet, the opposite of low diversity is software/IT sprawl, where too many vendors and supply chains increase administration challenges and multiply attack surfaces.

Another vital lesson from this landmark incident runs counter to the advice that countless cybersecurity agencies keep harping about: “Patch your systems as soon as possible!”. In this instance, automated patching built into the EDR system led to the simultaneous outage of millions of Windows machines worldwide. According to one expert on social media, this incident is a stern reminder that system and software patches are susceptible to injection attacks, human error, insider and systemic errors. All patches should be pre-tested on sandboxed systems and certified safe before a gradual, controlled rollout.